The Uncurious Case of Adam McKay, by Tyler Smith

18 Dec

It may have helped his career and general pedigree, but it would seem that the worst thing for director Adam McKay’s artistic sensibilities was winning that Best Adapted Screenplay Oscar in 2016 for The Big Short. In rewarding his comedically-anarchic approach to would-be dramatic material, the Academy essentially communicated to McKay that his throw-everything-at-the-wall instincts were much more of an asset than a liability. And while it can be refreshing to portray harrowing real life events in a humorous fashion – see Armando Iannucci’s The Death of Stalin as a recent example – it can lead to an unevenness of tone and execution that amounts to a sort of thematic wheel-spinning; making a lot of noise, but ultimately going nowhere. This is most certainly true of McKay’s new film, Vice, which purports to portray what lay behind the actions of former Vice President Dick Cheney. The instincts that may have served McKay well with the event-centered Big Short fail him here, as his attempts to make an illuminating character study are undercut by his own incredulity. The final product is a film that is self satisfied, condescending, and – perhaps worst of all – exceedingly uncurious.

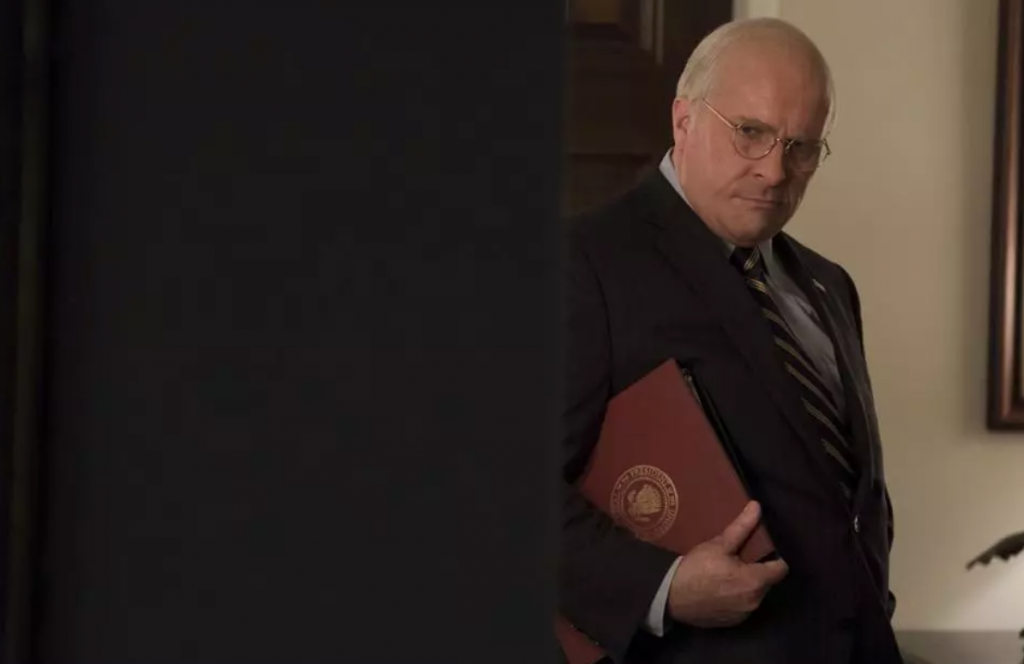

The film follows Cheney (played with mannered restraint by Christian Bale) from his early days as a hard-drinking roughneck to political power player, and eventually to the White House. Along the way, Cheney encounters cynical D.C. insiders like Donald Rumsfeld (Steve Carell), wary military men like Colin Powell (Tyler Perry), and ultimately the soon-to-be George W. Bush (a fun Sam Rockwell). Throughout it all, Cheney is supported by his ambitious wife Lynne (Amy Adams, in full Lady Macbeth mode), as they both try to navigate the murky waters of the political machine. This leads Cheney to masterminding the invasion of Iraq in 2003 and the vast expansion of executive authority.

All of this may sound fairly straightforward, but McKay’s depiction of these events veers wildly from absurd to realistic. He at times feels at war with himself, unsure of exactly what tone to strike. He is clearly angry, and his apoplectic rage definitely comes through, but often at the cost of a genuine desire to get at the core of Dick Cheney and those like him. Such curiosity is an important part of any biopic, but is positively vital to one about such a controversial public figure. It is what made Oliver Stone’s Nixon such a fascinating film; he, too, undoubtedly disliked his subject, but nonetheless felt a responsibility to try to understand him. The result was a film that made no excuses for the disgraced former president, but was clearly fascinated by what made him tick.

You’ll find no such fascination in Vice, sad to say. Instead, the film plays like an editorial in a college newspaper; hyperbolic, histrionic, and so very, very sure of its own inherent rightness. There is no desire to understand Cheney; only condemn him. And, indeed, many of his actions are worthy of condemnation, but we already knew that. What we don’t know is how a young man who the film states wasn’t a particularly brilliant student could have such a mind for the minefield of modern politics. We don’t know why exactly the idea of invading Iraq held such appeal for him. We don’t know what instilled in him such a sense of family loyalty that he actually stood by his daughter when she came out as gay.

There are a lot of things that we don’t know at the beginning of the film, and we continue not knowing them at the end. In McKay’s desperate desire to depict the infuriating actions of Cheney, all played with comedic commentary, he has made a film that is no more objectively illuminating than a Wikipedia entry.

McKay’s unfocused rage not only undercuts the deeper drama of his story, but also dumbs it down considerably. While there are moments of ambitious brilliance – such as a Shakespeare-inspired conversation between Cheney and his wife as they consider George W. Bush’s offer of the vice presidency – there are many more of hamfisted, on-the-nose laziness. One such moment features political novice Cheney asking Rumsfeld, “What exactly do we believe?” Rumsfeld responds to this with hysterical laughter, as if the very idea of Rumsfeld and his Republican cohorts actually believing in anything is so obviously ridiculous that one can’t help but laugh. This is treated in the film as incisive commentary, but all I did was roll my eyes. Later in the film, we hear Cheney’s inner monologue as then-candidate Bush explains his political platform. The first thought Cheney has? “He’s trying to impress his father.” Again, McKay plays this as a thought-provoking critique. Meanwhile, this analysis of Bush’s actions is nothing new, but the director seems to think that he’s blowing our minds.

But such is the danger of creating from a place of anger. It can blind the artist to their own biases and weaknesses. Certainly, many of the best works of art have come from a place of deep rage, but the passion of the artist can only go so far. To keep the work from flying off in all directions, it requires discipline and at least a nod toward objectivity; the understanding that the artist could actually be wrong in their assessment of their subject. When filtered through this humility, much of the superfluous frustration falls away, but what remains tends to have a laser focus, which will come through in a very consistent tone.

Even messier projects like Darren Aronofsky’s mother! and Boots Riley’s Sorry to Bother You, flawed though they may be, had a much clearer vision than Vice. Instead, McKay follows his rage wherever it goes. And, unsurprisingly, it goes places that are blunt, broad, and obvious. Even if the film were purely meant as satire, it falls short. The best satire acts as a sort of scalpel, slicing with surgical precision. Vice, however, is a shotgun, blasting away at its targets brutally and indiscriminantly, and eventually shooting itself in the foot.

Perhaps if Adam McKay had not won that Oscar, things would have gone differently. Maybe he wouldn’t feel quite so sure that his instincts were correct, and he’d take another look at his script. Maybe he would have realized that there was nothing particularly insightful about what he undoubtedly saw as a penetrating character study, and he would have made the proper changes. Maybe he would have opted to make a documentary or a straight-up comedy, where his sensibilities would heighten the commentary instead of hamper it.

Sadly, though, this was not to be, and we are left with Vice, a film that could have been every bit as incendiary as the best works of directors like Oliver Stone and Spike Lee. Unfortunately, due to the excesses – and obvious self satisfaction – of the director, it is an exercise in the worst kind of superficiality; the kind that is absolutely certain of its own depth.

No comments yet